In the fall of 2007, a 20-year-old student named Amanda Knox was studying abroad in Perugia, Italy, and living with three roommates. One was the British student Meredith Kercher. Only two months after she arrived, the unthinkable happened: Kercher was raped and murdered in the cottage where they all lived.

Along with Raffaele Sollecito, a man who she’d been seeing romantically for only a week, Knox was accused of Kercher’s murder without any forensic evidence. The subsequent investigation and trial took two years, where prosecutor Giuliano Mignini “presented a baseless theory of a sex game gone wrong, a drug-fueled orgy that devolved into murder,” as Knox writes in her new memoir, Free. Knox was portrayed as “a cunning manipulator, a sadist in sheep’s clothing.” She spent four years in prison before she was released, and then nearly four more years until she was acquitted of all charges. A man named Rudy Guede was ultimately convicted of the murder.

After these experiences, no one would have blamed Knox for pursuing a campaign of vengeance against her prosecutor, or vowing never to speak to him again.

X

Instead, Knox chose a counterintuitive strategy: turning toward her prosecutor with curiosity.

She reached out to him with a letter. As she got to know Mignini as a complex human, she began to cultivate compassion for someone “whose actions had derailed my life, irrevocably warped my image in the world’s eye, and invited the demon of despair into my life.”

Her family was appalled: “Why on earth do you want to talk to that monster? After what he put our family through?” As family members privately slung insults at Mignini, Knox felt an unspoken barb: What is wrong with you, Amanda?

She understood her family’s anger at this man. But she also knew “they were speaking from a place of hurt and judgment, and that if I gave into those impulses, I’d remain forever stuck in a prison cell of grievance.”

I spoke to Knox about how compassion and curiosity allowed her to break through that “prison cell of grievance,” finding models of forgiveness outside of religion, and the paradoxical relief she found in abandoning hope. Here is the conversation, edited for clarity.

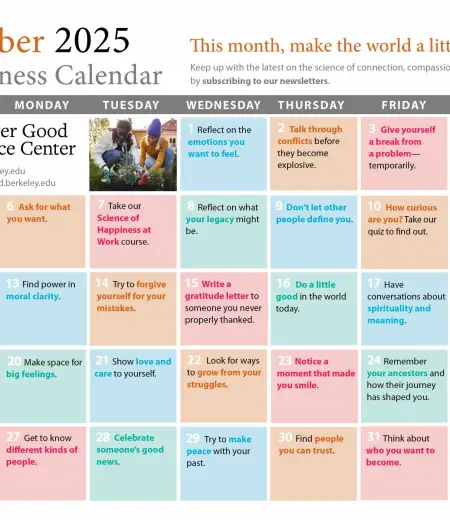

Elizabeth Weingarten: To start, I wonder if we could go back in time before your experience in prison and explore the origins of forgiveness in your life. How do you remember first learning about forgiveness?

Amanda Knox

Amanda Knox: I’m often asked about forgiveness as if I’m a “forgiveness expert.” It’s funny because I feel like I wasn’t setting out to forgive anybody. It’s more like forgiveness crept up on me. I came to a place of forgiveness from an indirect route, which I think is interesting because forgiveness often seems like such an intentional thing.

Looking back at my life, I don’t feel like the word forgiveness was instilled in me in some big way when I was a kid. Instead, what I remember learning was asking for forgiveness as opposed to giving forgiveness.

I was a tomboy as a kid, so I was always wrestling with the boys, and sometimes someone would get hurt. I remember learning to say, “I’m sorry,” for the times where I was the one who did the hurting. But I don’t remember anyone really teaching me how to be the one to receive that. Forgiveness was something you asked for; it was not something that you gave. I didn’t come from a religious family where [seeking forgiveness] was a sacred exercise.

I also should acknowledge that basically no bad things ever happened to me in my life before Italy. There were little petty things that of course happen to everyone, but in terms of big painful things, that was not something that I experienced. Going to Italy, this horrible thing happening, and these horrible things that kept successively happening—building trauma after trauma upon trauma—that was my first experience of something really bad and really harmful happening to me.

From what I understood [from previous life experience], when someone got hurt, it was usually an accident, and people felt bad about it. And so here I was interpreting what was happening to me as somebody making a big mistake, and eventually they were going to figure it out and feel bad about it. But the years went by and kept going by, and the people who had the power and were doing the harm were not figuring it out.

I struggled with that my entire adult life: Not only am I being actively vilified, my life just ripped to shreds, but the people who did it to me didn’t seem to care that they were hurting me and that they were wrong. That was really hard for me to wrap my mind around. I think struggling with that and not understanding why left this deep wound in me that I sought closure from.

Free: My Search for Meaning (Grand Central Publishing, 2025, 304 pages)

I sought healing in the form of reaching out to those people, primarily my prosecutor, the one who was in charge of the entire investigation.

I was just thinking, “Doesn’t he know [that I’m innocent]? How could he not know?” Part of me was curious: If he did know, why was he holding back from doing the right thing? Could I somehow convey to him, “I am not a monster, and you were wrong about me. I’m not trying to make you feel bad. I’m just wanting you to know that was a huge mistake, and it hurt me.”

Almost more than forgiveness, it was curiosity that drove me. I wanted to understand him, and I wanted him to understand me.

The interesting thing for me is that the forgiveness thing comes into play when you get to know a person. When you really come close to a person, it changes the way you feel about them, and it changes the way you feel about the hurt that was done to you.

I didn’t forgive him in the sense that I didn’t just say “what you did wasn’t a bad thing.” It was in no way undermining my experience of being harmed. Instead, it was reinforcing the idea that harm can result even from the best of intentions. You can’t hate someone for making a mistake.

And for me, it was really important to acknowledge that. Acknowledging the truth necessarily put me in close contact with this person who I then started to feel compassion for. That’s a natural result. That compassion sort of morphed into forgiveness. Curiosity and compassion combined equals forgiveness for me. That’s how it sort of came about in this roundabout way.

“Curiosity and compassion combined equals forgiveness for me.”

EW: This seems like a key barrier to resistance for so many people: not taking the time to know the person who wronged you, in order to feel that compassion and shared humanity.

I want to dig into something else you mentioned—that forgiveness wasn’t part of a religious upbringing for you. Many of us do come across concepts of forgiveness from religion; it’s not as prominent, for instance, in ancient philosophical texts as it is theological ones.

I’m curious, given the secularization trend across American society, how you think about the evolution of forgiveness right now? Are we living in a moment where forgiveness has gone out of style, or how do you think about forgiveness in the context of our culture?

AK: You’re right, I don’t think that forgiveness has been given a lot of weight in the secular space, outside of a therapeutic context. [There], it’s not even about forgiving [as something for] the other person. It’s for you, right? It’s a gift-that-you-give-yourself kind of thing. It’s certainly not expressed as a form of compassion [for someone else].

I think it’s a shame that we’ve lost, or we’re not recognizing, the weight of it. I don’t want to use the word “sacred” because that’s the faith word for it, but how do you convey that there’s tremendous value to compassion? And to the expressions of compassion that we have available to us, and how they are good not just for ourselves but also for other people?

There’s a lot of divisiveness and communication about how we are in opposition. In the secular world, it seems like there’s less of a language and an exercise for coming back into connection after we have found ourselves in opposition or in an adversarial space. There’s more space for that in the religious context because there is more acknowledgment—especially in the Christian context—that we are all imperfect, right?

There is something really compelling about this idea that we are all marked by sin. None of us are going to exist in the world without making mistakes and without potentially hurting somebody. People have interpreted that in wildly unethical ways, but the more real and generous interpretation of that is that none of us is perfect. We all make mistakes, and we all therefore are in need of some kind of reconciliation with ourselves and with others.

The exercise of reconciliation is something that I’ve been attempting to find in my life in a secular space. And what I found is I’ve had to invent how to do it. There wasn’t really a straightforward path in a secular space for me to achieve what ultimately was an act of forgiveness, because I didn’t see that reflected in the secular world around me. The secular world around me really crystallized people, stuck them in amber, and their choices became defining of them, instead of seeing that everyone is a process, everyone is an evolution, everyone is in a context with each other and informed by each other.

“The secular world around me really crystallized people, stuck them in amber, and their choices became defining of them, instead of seeing that everyone is a process, everyone is an evolution, everyone is in a context with each other and informed by each other.”

I don’t think it’s a mistake that my process of reaching out to my prosecutor and trying to reconcile with him also coincided with me becoming a more spiritual person. I practice Zen Buddhism, which doesn’t have anything specifically about forgiveness in its language, but it’s more about recognizing that we are all connected. As a result of that, it really matters that when something harmful happens, we seek reconciliation, and that it takes two; it’s not just a one-way street. It is absolutely a reciprocal act of acknowledgment.

EW: I want to talk for a moment about agency and power, which is a prominent theme for you. You write about a time when you were considering ending your own life, but you choose instead to live and, in your words, to suffer. You write:

That choice gave me a sense of responsibility for the shape of my own life. As much as others were to blame for putting me in that cell, for sending me death threats, for ruining any possibility of a quiet, anonymous life, it was my choice to accept all that or take the emergency exit. And if it was my choice, then blaming the world made little sense. Realizing that made it easier to accept my life and find a way to fill it with beauty, love, knowledge, to kindle the fragile light of truth in that long dark tunnel…I began to ask myself, “How do I make this life worth living?”

And then you start to ask, “How do I make this life worth living today?”

I love these questions and this way of thinking about the responsibility we have in our own lives: both not letting people off the hook for what they’ve done to us, but also accepting the role that we play in our own freedom from allowing those actions to limit our own sense of meaning and peace. How has forgiveness played a part in answering those questions for you?

AK: One of the things that I realized, especially after my conviction, is that I was limited by a lot of things. I was stuck in a jail cell, not of my own volition. So, there were very real limitations placed around me.

But I wasn’t just limited by that. I was limited by my own mind and my own inability to recognize that even within the limitations that had been placed on me, there were opportunities to live and to thrive that hadn’t been taken from me because I had my own mind. I still had the ability to interact directly with the people around me. And so, within that space, there was opportunity.

When I say that I was limiting myself, even the first two years of my imprisonment, I was really stuck in this mindset that I didn’t belong there, and I had to hang on and wait to get my life back. The waiting went from weeks to months to years, but it was still just a matter of bracing myself and clinging to little ways I could cling to my real life that was outside of the prison.

So, writing tons of letters and doing my one visitation a week and my one phone call a week—those were when I actually lived. Everything else in the meantime was just waiting to live. That was a limitation that I was imposing on myself. I could have been living all of that in-between time if I had been able to recognize that there was an opportunity for me to live and to thrive even within those limitations.

It was after I was convicted and confronted with having to actually spend decades in prison that I was like, “OK, my life isn’t out there. It’s in here. So, what does living in here look like?” And, again, it wasn’t fair that that was my life, but that’s just what it was.

I wouldn’t say that forgiveness of the people who did this to me played a role in it. I think it was more forgiveness for myself. I felt so stupid. I felt like my life was wasting away not just because of other people’s choices but because of my own. So I had to forgive myself and let that go and also exist in a world around me that was really difficult.

I was surrounded by people who were very, very broken. Sometimes that made it really difficult to just live a day-to-day existence with them. But I also realized that they deserved forgiveness, too. They had histories of abuse and violence and neglect and poverty. That informed their decisions to commit crimes and to be emotionally and mentally unstable as much as anything else.

Learning to live with human fragility necessarily requires forgiveness because we’re all making mistakes. We’re all doing our best and screwing up. Being plunged into a world full of faulty people led me to appreciate that the people who have made the biggest mistakes have a context, and there is room for compassion even there.

EW: You write so beautifully about compassion in your book: “It is not kindness if it is reserved for the kind; true compassion, true mercy must be extended to everyone and perhaps especially to the people who have hurt us. Only then can we be free.” Obviously, your experience in Italy was such a central part of what has shaped your perspective on this, but I’m also wondering how, if at all, becoming a mother has contributed to it.

AK: I mean, tremendously so in the sense that it’s all about human connection. The thing that harm does is it disconnects you from people. It’s an act of tearing the social fabric. And we do not exist as an island. We are all interconnected. We are all interdependent.

When harm is expressed, the person who is hurt, out of a sense of defensiveness, will pull away from society. I experienced that on two levels: I was being hurt, and so I was pulling away, and my compassion was being tested because I was being actively hurt. But then also people were isolating me and exiling me and ostracizing me because they viewed me as a harm-doer, and so I was being expelled. I was sort of being expelled from humanity from both sides. I felt really estranged from other people. I think I recognized that that was a very dangerous place to be because, exiled or not, we all are interconnected. We’re all interdependent. If you’re exiled, you don’t function. You can’t function and you can’t thrive.

When I got pregnant, I felt a sudden sense of urgency to figure out this problem of human connection in my life, because I know that unconsciously I carry a lot of pain inside of me. Now I wasn’t just carrying pain; I was carrying a child. And I didn’t like the feeling that I was carrying both of those things at the same time—that somehow I might be poisoned, that I was not a healthy vessel for my child who was utterly dependent upon me.

“When I got pregnant, I felt a sudden sense of urgency to figure out this problem of human connection in my life, because I know that unconsciously I carry a lot of pain inside of me. Now I wasn’t just carrying pain; I was carrying a child. ”

I was her first human connection, and now I am the conduit through which she is going to emerge into the world of human connection. And how can I be the best possible conduit if I’m disconnected?

I felt this immense amount of urgency to reaffirm human connection and to really follow my gut instinct towards compassion. In so doing, I sort of realized in my life a better, safer, healthier space for my daughter to exist in than I felt I was allowed to exist in.

EW: Part of your forgiveness journey also meant letting go of the idea that through forgiving Giuliano you would get something in return—understanding, acceptance. You talk about how, prior to seeing him in Italy, you had to abandon all hope. I think some people might hear that and think, “that sounds really bleak,” but you write that it made you “invincible.” What do you think are the benefits of letting go of all hope?

AK: It’s this paradoxical thing where it sounds so bleak, but it’s actually so liberating. Instead of focusing on what you lack, you focus on what you have, and especially what you have in abundance. So instead of focusing on the olive branch that he could give me, I focused instead on the olive branch that I could give him. As soon as that flip happens in your mind, nothing can hold you back. It completely reverses the scenario where suddenly you are the one who has all of the power, and that feeling of helplessness and desperation just completely disappears.

There’s this saying in Zen that “you are perfect, and you could also use improvement,” which is really embracing that paradox of “you are enough.” You have everything you need. Of course, would it be great if other things transpired to make you whole and to heal? But also, right now, you are enough, and you have everything you need to accomplish what you need to accomplish.

For me, it was abandoning this idea that I needed something in order to be whole. I was whole, and I was more than whole. I had something to give, and that propelled me forward and continues to propel me forward, even when there are still aspects of my life that are unresolved. I think it’s really an important lesson for all of us, because we’re never going to have everything resolved.

EW: How would you describe the relationship that you have to Giuliano, your prosecutor, at this time? And the relationship you have to yourself in terms of that forgiveness journey that we’ve been talking about?

AK: I know that for him, I am a source of great comfort. I think he really has grasped this sense of absolution that he’s gotten from me. It’s interesting because on the one hand, he doesn’t necessarily admit to any explicit wrongdoing, and yet he also seeks absolution. So there’s something there that he’s getting that maybe he’s not fully conscious of that is meaningful to him. I know that because he tells me constantly that it is meaningful to him that I’m willing to recognize the positive aspects of his humanity.

As far as my relationship to myself, I trust myself. I’ve learned a lot of hard things the hard way, and now I know myself very well. I know what my weaknesses are. I know how much I can bear and what I don’t need to. That puts me in a position of knowing when to set boundaries, knowing what expressions of myself give me energy, which drain. All of that has been the result of risk-taking and, as I said, learning a lot of hard things the hard way. I’ve been pushed to a lot of my extremities, and I’ve had to endure a lot of things for extended lengths of time. So I know what I’m capable of—and I trust myself.