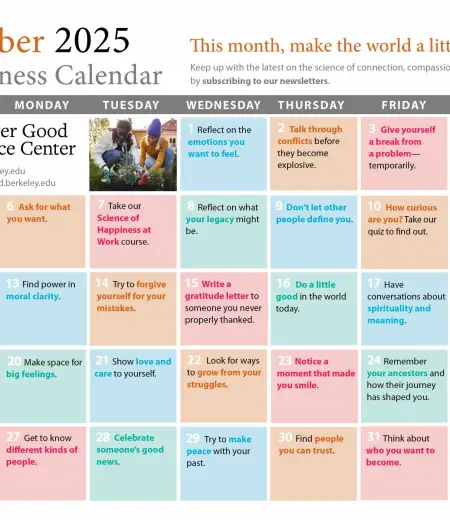

Uncertainty is part of the human condition. Because we are able to draw upon our memories and knowledge to imagine different futures, life can come to seem like a guessing game that never ends. That can create anxiety, which can metastasize into rumination and paralysis.

In her new book, How to Fall in Love with Questions , behavioral psychologist Elizabeth Weingarten reveals her personal and intellectual struggle to live with uncertainty, and perhaps even embrace it. I spoke with Elizabeth about the solutions she discovered at an event at Berkeley’s Book Society. Here is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Jeremy Adam Smith: Where did this book begin?

X

Elizabeth Weingarten: Like many people, at one time I was dealing with a lot of uncertainty in my life. For me, this came in two distinct flavors.

I had recently gotten married, and I was questioning my marriage, to say the least. So, I was grappling with this question of, Should I get a divorce?

The other big question involved my work. I had recently left a job and I was pursuing a creative project, and it was becoming very clear that this creative project was completely failing to launch. All of a sudden I was asking: What am I doing with my life?

I put all my eggs in this basket, and it was not panning out. To face this uncertainty, I was listening to lots of podcasts, I was reading lots of self-help books. I was trying to find answers to these big questions that felt really scary and really heavy—and, frankly, it felt very lonely to be dealing with them at the same time.

Across all of these books and podcasts that I was reading, I kept coming upon the same advice, and that advice was just “embrace uncertainty.” And to me, this felt just very tone-deaf, because I think it’s one thing to embrace uncertainty in like fun, exciting moments in your life, like maybe you don’t know what your family’s planning for your birthday. But try telling somebody who’s waiting on the results of a biopsy to embrace uncertainty. Try telling somebody who you know is dealing with the death of a loved one to just embrace uncertainty. That felt to me like a kind of toxic positivity.

There are these moments in life that, to me, call for a very different way of relating to uncertainty. It was around that time that I found a book called Letters to a Young Poet. That’s a book of correspondence between the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke and this aspiring poet named Franz Kappus that was published in the early 20th century. Kappus was 19 when he was writing to Rilke, and he was asking Rilke all kinds of questions about how to live his life, as many of us do when we’re 19. And Rilke, very famously, responded to him not with answers, but with this advice that has become timeless and enduring. He tells him to “love the questions themselves,” as if they were locked rooms or books written in a foreign tongue, and Rilke encouraged Kappus not only to love the questions, but to live the questions.

So, I’m reading this book, and on the one hand, I was really struck by this passage. By the way, this is a book that has a very interesting following. Dustin Hoffman has called it his Bible. Lady Gaga has a line from it tattooed on her. I loved this idea of loving the questions, and yet I had never felt further away from loving the questions of my life. I hated the questions.

My book really came out of this question that I had, which was: What does it actually mean to love the questions of our lives, particularly the questions that are really painful and challenging to love? How do we start to do that? How do we do that in a time in which so many of us have become addicted to fast, easy answers?

JAS: What is uncertainty, psychologically speaking, and why do we resist it?

EW: My favorite definition of uncertainty is a sense of doubt that stops or delays progress. That came from a couple of psychologists who were writing a paper about how decision-makers cope with uncertainty.

I like this definition because I think it gets at the lived experience of uncertainty. For many of us, when we don’t know the answer to a question, we feel stuck. We feel stopped and stagnant in our lives until we find the answer and feel like we can move forward. I also found that we as humans are really wired to avoid uncertainty and seek certainty. And a big part of the reason for that is because it’s more metabolically costly for us to deal with uncertainty.

We evolved during a time of food scarcity. Since it takes more energy to navigate uncertainty, we learned to prefer certainty in our environment. That’s what’s known as selfish brain theory. That’s one part of why we want to get the answer to our questions and feel really uncomfortable when we don’t have those answers.

JAS: Do you feel like we as a culture are becoming less tolerant of uncertainty?

EW: There’s some research from Nicholas Carleton, at the University of Regina in Canada, which shows that as smartphone and Internet penetration has increased, so too has our intolerance of uncertainty. We’re talking here about correlation, not causation, so we can’t say definitively that phones are the cause. But Carleton’s research does suggest that there’s a connection, and the reason why he and other researchers think that there’s a connection is because with our smartphones, all of the sudden, we’ve lost all of these moments during our day and our lives to practice dealing with uncertainty.

Think about how when you go to a restaurant, you Google the menu. I do this all the time, right? You’re like, I gotta know what I’m gonna order before I go. Or if you’re going to a new city, you spend a lot of time on your phone mapping out all the places that you’re gonna visit. Or maybe you’re just in a moment where you’re kind of feeling uncomfortable or anxious, and you turn to your phone to try to numb that feeling.

If you think about uncertainty tolerance as a muscle, there are all these moments when we could be strengthening it in little ways, but we’re actually atrophying it, because all of a sudden we have in our pockets these little false certainty devices that are giving us the answers to all of these questions over time.

JAS: You start the book talking a lot about cults and cultish behavior and cultish ways of thinking, which I thought was pretty interesting. Why did you start there?

How to Fall in Love with Questions: A New Way to Thrive in Times of Uncertainty (HarperOne, 2025, 320 pages)

EW: One of the things that I talk about at the beginning of the book is this idea that it is increasingly difficult to love the questions and live with the questions. And what I mean by that goes back to Rilke’s idea of trying to sit with and exist in and have a different relationship to uncertainty.

Before I talk about cults, I want to explain this framework at the beginning of the book where I liken different questions to different parts of a fruit tree. If you think about questions as ripening into answers, you can think about one type of question as being like a peach type of question, one that ripens pretty quickly into an answer.

The second type of question might be a pawpaw question, as in pawpaw fruit. That is a type of fruit that actually can take five to seven years to ripen, so a pawpaw question might be something like, Is this fertility treatment going to help me have a kid? Or maybe, Will I really like this career change that I’m making?

The third type of question is a heartwood-style question. Heartwood is the core of the tree that stays with the tree over the course of its entire life. You have different layers that grow around the tree, but the heartwood is what gives the tree its stability and security over time. So, these are the questions that really stay with you. These are the questions like, Who am I? Who am I becoming? How do I live a life of meaning and purpose? A lot of the book deals with the heartwood-style questions, about love, loss, purpose, relationships.

The final type of question is the dead-leaf question. These are the types of questions that are no longer serving us, that we may be better off letting go. These are the types of questions that are keeping us locked into patterns of regret and rumination. Sometimes these are questions keeping us locked in the past, when ultimately we want questions that are helping us to move forward.

What does that have to do with cults? Heartwood and dead-leaf questions can be really heavy, challenging questions to carry and hold alone. That creates fertile ground for what I call the charlatans of certainty. Those are the gurus, or influencers, or experts, who want you to believe that they have all of the answers to the biggest and most important questions in your life. Cult-like groups are an extreme example of that. They’re often successful because they lead their followers to believe that they have all the answers, and that you have all this uncertainty and all this fear and all this pain in your life—but if you just join us, all of that will go away. All of your doubts will evaporate.

And of course, nobody can do this, right? No group, no person can do this. I start out talking about the research on cults and certain cult-like groups and the charlatans of certainty because all those phenomena can be really, really challenging for people who are trying to love the questions of their lives.

JAS: How do you know if a question is a good one? How do you build a good question?

EW: The answer boils down to this: Is your question opening you up to lots of different possibilities in your life, or is it limiting you, or closing you off?

Take one of the questions I started with: Should I get a divorce? That was not a good question, because it was a binary. It’s either yes or no. I’ve learned that a really good question breaks you out of binaries, and it helps you see a whole landscape of possibilities for what an answer could look like for you. And so for me, a better question might have been something like, What would have to change in order for us to stay together? Or, How might we make this relationship work? Ultimately, shifting that frame gave me and my husband the space we needed to actually have the right conversations to be able to move forward.

The other really key component to what makes up a great question is this: Is your question serving as an internal GPS? What I learned from many people that I interviewed for this book—activists, scientists, some Zen Buddhist practitioners, all kinds of people across the gamut of different expertise—is that for your question to be a great question, it needs to lead you back to yourself and what you want from your life. It is not someone else’s question, and it does not tie you to someone else’s expectations for what they want of you.

So, I think to find a good question, you need to ask yourself: Is this even my question—or is it someone else’s about me? Do I even want to be asking this question?

I’ll give you an example of a question that I’ve been living with and working on recently: Am I having a second kid? A lot of people in my life are asking me this question! But is it the right one for me? And note that’s a very yes-or-no binary question, one that closes off possibilities rather than opens them up. I’ve started reframing this question for myself as: How will I know if I want to have a second kid or what will it look like? What are some of the things that I can look for if I do want that?

Then I think you have to ask if your question is a dead-leaf one that keeps you stuck in the past. Those are the questions that leave us spinning: Why didn’t I do that? Why did I break up with this person? What if I had just done this or been that way? Instead you need to ask yourself: Do I feel like this is moving me forward toward an answer in my life, or does it feel like it’s keeping me stuck and locked in a past that I can no longer control? If your questions keep you stuck in rumination patterns, if they’re no longer moving you forward and no longer making you feel excited about future possibilities, you probably want to let them go.

JAS: It occurs to me that we live in a culture that poses questions that people in previous periods in history could never ask, because of social pressures or even laws, like: Should I stay with my husband? That’s not really a question a lot of women could ask themselves, in many times and places. Once you answered that kind of question—assuming you were even allowed to ask it—you were done, because divorce wasn’t an option. Should I take that job and move to another city?—that’s not something farmers asked themselves in feudal economies.

Today, we don’t live that way; we’re in a much more mobile, fluid society, facing uncertainties that our ancestors never did. Today, there are some questions you just have to never stop asking—the heartwood questions, I guess. Should we ever stop asking if we should stay with our spouses, even if the answer is always yes? It strikes me as actually being somewhat functional to always hold that question, and yet, also, it’s kind of crazy-making.

EW: Yeah, it gets to the question of: Can we ever ask too many questions? Is there a time when it becomes overkill? Especially in a relationship, it can become neurotic and nit-picky to continuously question whether you’re meant to be together. And, as you say, crazy-making.

But take this question of whether you should be with your spouse. It’s not necessarily about whether you should continue to ask it or not, but also: Is that the only question you’re asking in your relationship? Are there other questions that aren’t binaries, that can help you come to know each other better or differently, that can help you grow?

To me, it’s right to think about relationship questions as being heartwood questions, because these are the questions that are maybe never permanently answerable across your life, right? And so maybe they’re questions that you have and answered for a certain time, but with any really significant relationship, I think it would be very odd to say, Well, we got married, and now this it for the rest of our lives. I think commitment is worth interrogating throughout your life, as long as you are also asking other generative questions alongside it.

JAS: If only to renew that commitment, so we don’t end up sleepwalking.

EW: Right. The sleepwalking to me is a symptom of curiosity being dead in a relationship. Not only are you not asking the question of whether you should be together, but you’re also not asking an assortment of other questions: Who are you to each other after a big life change? How do you continue to learn about each other even when it feels like the other person is entirely known (when, generally speaking, they aren’t)?

The key is to keep curiosity kicking—something we can do with a shared commitment to asking better questions.